Should Spark have an API for R?

Table of Contents

- The SparkR API: DataFrames are confusing

- Functionality, adoption, and commit velocity

- Inability to plot data

- Visibility into debugging

- Incomplete Documentation

- Conclusion

Goya, Fire at Night

Goya, Fire at Night

As a consultant, I’m often asked to make tooling choices in big data projects: Should we use Python or R? What’s the best NoSQL datastore right now? How do we set up a data lake?

While I do keep up with data news, I don’t know everything that’s going on in the big data ecosystem, which now sprawls to over 2000 companies and products, and neither does anyone else working in the space.

In an effort to make all of these parts accessible to different audiences, developers create APIs that the majority of data scientists already use, namely by making their code accessible to R and Python interfaces.

A number of products are based off the success of tooling for these two languages. Microsoft, for example, offers R and Jupyter notebooks in Azure Machine Learning. Amazon offers Jupyter notebooks on EMR. And, in my favorite example about how everyone is trying to get on the data science bandwagon, SAS now lets you run R inside SAS.

One project that has been particularly good at staying ahead of the curve is Spark, which began in Scala and quickly added a fully-functioning Python API when data scientists without JVM experience started moving to the platform. It’s currently under the aegis of Databricks, a company started by the original Spark project developers. It provides, of course, its own notebook product.

The motivation behind SparkR, is great. If you know R, you don’t have to switch to Python or Scala to create your models, while also benefitting from the processing power of Spark. But, SparkR, as it stands now, is not (yet) a fully-featured mirror of R functionality, and I’ve come across some key features of the platform that make me believe that SparkR is not a good fit for the Spark programming paradigm.

The SparkR API: DataFrames are confusing

The first problem is data organization. Data frames have become a common element across all languages that deal with data, mimicking the functionality of a table in a SQL database. Python R, SAS all have them, and Spark has followed suit.

In general, tables are good. Tables are the way humans read data easiest, and the way we manipulate it. In relational environments, tables are pretty straightforward. But the issues start when imperative programming languages try to mimic declarative data structures, particularly when these data structures are distributed across many machines and linked together by complicated sets of instructions.

In Spark, there big difference between SparkDataFrames, and R’s data.frames.

Here’s a high-level overview of the differences:

To the naked eye, they look similar and you can run similar operations on them. There is nothing in the way they are named to tell you what kind of object they are. The difference between them became so confusing that SparkR renamed DataFrames to SparkDataFrames, in part because they were competing with the name of a third package, S4Vector.

But, to the person coming from base R functionality, there is a real clash of concepts here. data.frames are similar in the real world to looking up a single word in a dictionary. But with SparkDataFrames, the definition of your word is spread out across all of the volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and you need to search through each volume, get the word you want, and then piece it back together into the definition. Also, the words are not in alphabetical order.

It helps to examine each structure’s internals. To start with, let’s look at R data.frames.

An R dataframe is an in-memory object created out of two-dimensional lists of vectors of equal lengths, where each column contains values of a single variable and rows contain a single set of observations.

Working in RStudio, we can import one of the default datasets:

datasets() # display available datasets attached to R

data(income) # use US family income from US census 2008

help(income) # find out more about the package

income <-income # put the data into a data.frame

> class(income) # check type

[1] "data.frame

> class(income$value) #check individual column (vector) type

[1] "integer"

str(income) # check values

'data.frame': 44 obs. of 4 variables:

$ value: int 0 2500 5000 7500 10000 12500 15000 17500 20000 22500 ...

$ count: int 2588 971 1677 3141 3684 3163 3600 3116 3967 3117 ...

$ mean : int 298 3792 6261 8705 11223 13687 16074 18662 21064 23698 ...

$ prop : num 0.02209 0.00829 0.01431 0.0268 0.03144 ...

When you run operations on an R data.frame, you’re processing everything on the machine that is running the R process, in this case, my MacBook:

mbp-vboykis:~ vboykis$ ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

28239 ttys000 0:00.18 ~/R

A SparkDataFrame, is a very different animal. From Databricks:

First, Spark is distributed, which means processes, instead of happening locally, are broken out across multiple nodes, called workers, across multiple processes, called executors.

The process that kickstarts this is the driver. The driver is a program that kicks off the Spark session and creates the execution plan to submit to the master, which sends it off to the workers. In simpler terms, the driver is the process that kicks off the main() method.

The driver creates a SparkContext, which is the entry point into a Spark program, and splits up code execution on the executors, which are located on separate logical nodes, often also separate physical servers.

You write some SparkR code on the edge node of a Hadoop cluster. That code is translated from SparkR, to a JVM process on the driver (since Spark is Scala under the hood.) This code then gets pushed to JVM processes listening on each edge node. In the process, the data is serialized and split up across machines.

Only at this point, once Spark has been initialized and there is a network connection, a SparkDataFrame is created.

Really, a SparkDataFrame is a view of another Spark object, called a Dataset, which is a collection of the serialized JVM objects objects.

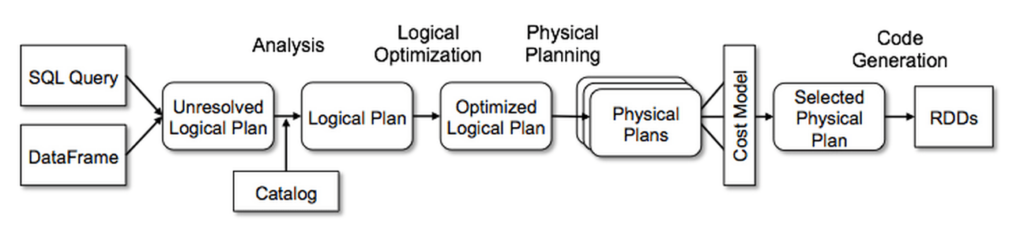

The Dataset, the original set of instructions created by translating the R code to Spark, is then formatted in such a way by SparkSQL as to mimic a table. There is an great, detailed talk about this process by one of the SparkR committers.

Additionally, for a SparkDataFrame to compute correctly, Spark has to implement logic across servers. To make this work, the SparkDataFrame is not really the data, but a set of instructions for how to access the data and process it across nodes, the data lineage.

Here’s a really good visual of all the setup that needs to happen when you do invoke and make changes to a SparkDataFrame, from Databricks:

There are two major implications for this level of complexity is that you access SparkDataFrames differently than data.frames.

- Although Spark is a row-based paradigm, you can’t access specific rows in an ordered manner in a

SparkDataFrame.

head(income)

value count mean prop

1 0 2588 298 0.022085115

2 2500 971 3792 0.008286185

3 5000 1677 6261 0.014310950

4 7500 3141 8705 0.026804229

5 10000 3684 11223 0.031438007

6 12500 3163 13687 0.026991970

> class(income)

[1] "data.frame"

> income[row.names(income)==2,]

value count mean prop

2 2500 971 3792 0.008286185

And now the SparkR equivalent:

sdf <- as.DataFrame(income) #convert to SparkDataFrame

sdf #check out type

SparkDataFrame[value:int, count:int, mean:int, prop:double]

head(sdf) #same function as on local data

income[row.names(income)==2,]

Error in sdf[row.names(income) == 2, ] :

Expressions other than filtering predicates are

not supported in the first parameter of extract operator [ or subset() method.

That error comes from here, which means you can only do columnar operations to an initial DataFrame.

So, instead, you iterate over an entire SparkDataFrame as a whole, applying all the changes to what in R would be the equivalent of a vector.

This leads to really annoying workarounds to common R problems, like, for example, filling nulls. Let’s say you have a column of nulls, and in order to avoid outliers, you want to impute the average of the column and backfill it.

In an R data.frame, you could do:

m <- matrix(sample(c(NA, 1:10), 100, replace = TRUE), 10)

d <- as.data.frame(m)

V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V6 V7 V8 V9 V10

1 1 4 10 3 1 4 9 6 3 1

2 3 4 10 5 2 3 7 1 9 NA

3 10 NA 5 NA 10 9 3 NA NA 5

4 1 9 4 3 3 2 8 7 7 8

5 6 3 2 6 5 10 5 10 10 9

6 5 9 7 10 5 6 8 3 4 10

7 9 10 3 6 6 4 6 7 7 8

8 5 9 8 4 8 2 2 9 9 NA

9 1 5 1 8 7 3 8 1 NA 4

10 10 2 9 10 1 3 8 8 5 6

for(i in 1:ncol(d)){

d[is.na(d[,i]), i] <- mean(d[,i], na.rm = TRUE)

}

d

V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V6 V7 V8 V9 V10

1 1 4.000000 10 3.000000 1 4 9 6.000000 3.00 1.000

2 3 4.000000 10 5.000000 2 3 7 1.000000 9.00 6.375

3 10 6.111111 5 6.111111 10 9 3 5.777778 6.75 5.000

4 1 9.000000 4 3.000000 3 2 8 7.000000 7.00 8.000

5 6 3.000000 2 6.000000 5 10 5 10.000000 10.00 9.000

6 5 9.000000 7 10.000000 5 6 8 3.000000 4.00 10.000

7 9 10.000000 3 6.000000 6 4 6 7.000000 7.00 8.000

8 5 9.000000 8 4.000000 8 2 2 9.000000 9.00 6.375

9 1 5.000000 1 8.000000 7 3 8 1.000000 6.75 4.000

10 10 2.000000 9 10.000000 1 3 8 8.000000 5.00 6.000

In SparkR, you have to work around the fact that you can’t fill columns the same way (due to partitioning, you can’t aggregate.)

Here’s the error message:

Error in sdfD[is.na(sdfD[, i]), i] <- mean(d[, i], na.rm = TRUE) :

object of type 'S4' is not subsettable

In addition: Warning message:

In is.na(sdfD[, i]) :

is.na() applied to non-(list or vector) of type 'S4'

So you have to force a variable from SparkR and fill with the fillna, as a list, for every column:

mean(sdfD$v10)

your_average<-as.list(head(select(sdfD,mean(sdfD$v10))))

sdfFinal<-fillna(sdfD,list("v10" = your_average[[1]]))

sdfFinal

head(sdfFinal)

It’s arguably less code (at least for a single entity), but it’s much harder to understand, and it takes a lot of digging through the API to find these types of equivalents.

And, second, unlike R, which will return the same result set every time you want to display a data.frame, the distributed nature and partitioning process in Spark, means each pass at a SparkDataFrame returns a slightly different subset of data when you’re doing computations, depending on how quickly processes complete and how the data execution plan decides to act.

What happens when data is returned from Spark is really well-illustrated by this joke:

Some people, when confronted with a problem, think “I know, I’ll use multithreading”. Nothhw tpe yawrve o oblems.

To add to this confusion, you can switch between SparkDataFrames and data.frames and not even be aware until Spark throws an exception.

And you can write similar functions for both. So what is, in theory, a great feature, language portability, becomes a hassle, because you can have:

model <- glm(F ~ x1+x2+x3, df, family = "gaussian")

model <- glm(F ~ x1+x2+x3,data=df,family=gaussian())

Which one is R, and which one is Spark? If you forget syntax, it’s easy to get confused.

Which is why, a common practice I’ve seen is labeling our objects with sdf for SparkDataFrame and rdf for r data.frames.

sdfmodel <- glm(F ~ x1+x2+x3, df, family = "gaussian")

rdfmodel <- glm(F ~ x1+x2+x3,data=df,family=gaussian())

This gets confusing and a bit cumbersome if you end up creating a lot of objects, or having to pass objects from one environment to the other.

Which brings me to the second issue:

Functionality, adoption, and commit velocity

SparkR is young and, ostensibly, growing. That means that features are constantly being added. But SparkR, while growing, seems to be a lower-priority language in the Spark ecosystem.

You can see in Matei Zaharia’s slides at SparkSummit over the past couple years, that Databricks, the company now overseeing Spark development, is more concerned about catching up to the market for deep learning, streaming, and fine-tuning SparkSQL performance (which impacts Scala, Python, and R), than focusing on on the SparkR API.

This makes sense: only 20% of Spark language usage is in R,leading to a chicken-and-egg problem. Until that number grows, there’s no pressure to significantly up resources devoted to it. Until there are more resources devoted to it, the number of users won’t increase.

Aside from messaging from leadership, is there a way to tell whether SparkR development is increasing and whether it makes sense to use SparkR for a project? I pulled the SparkR codebase mirrored from Apache on GitHub to find out.

A cURl call tells us that SparkR makes up less than 4% of the overall Spark codebase (in lines of code):

# pull all languages used in the Spark repo

curl -u veekaybee -G "https://api.github.com/repos/apache/spark/languages"

Enter host password for user 'veekaybee':

{

"Scala": 22832829,

"Java": 2948574,

"Python": 2210161,

"R": 1047322,

"Shell": 155167,

"JavaScript": 140987,

"Thrift": 33605,

"ANTLR": 32969,

"Batchfile": 24294,

"CSS": 23957,

"Roff": 14420,

"HTML": 9800,

"Makefile": 7774,

"PLpgSQL": 6763,

"SQLPL": 6233,

"PowerShell": 3751,

"C": 1493

}

Granted, this itself isn’t an indicator of anything. There are a couple of theories here:

Most of the interop code to get R to run with Scala is written in Scala. Looking at the Python codebase, we see a similar pattern: In spite of how prevalent PySpark usage is, it makes up only 7% of the Spark source code.

SparkR development started very recently, and will take a significant amount of time to catch up to the volume of code written in Scala.

R is more terse than Scala or even Python and requires less LOC to get the job done.

To dig a little further, I cloned the Spark repository and parsed out the Git logs in Python. Script available here.

This worked pretty well, since the commit messages are really well-organized and tagged (at least, since 2013 ;), as a result of Spark’s extensively documented contribution process and standardized pull request language:

The PR title should be of the form [SPARK-xxxx][COMPONENT] Title, where SPARK-xxxx is the relevant JIRA number, COMPONENT is one of the PR categories shown at spark-prs.appspot.com and Title may be the JIRA’s title or a more specific title describing the PR itself.

Checking out the pull request categories on the reference site,reveals a ton of work being done in SQL, and not as much in R, but there is no spatial or time element, meaning it’s again hard to evaluate.

Here are the total commits to the Spark project over time:

And here is PySpark vs SparkR:

I left out 2017 since it’s not complete yet. Surprisingly, visually there seems to be more activity in SparkR than PySpark over the same period. This in itself is also not indicative of anything specific. Does it mean that more resources are being devoted to it, or that it’s so far behind that more commits are needed to catch it up?

Once again, hard to tell. But, when working with R, it’s easy to intuit that there are a number of features in R that are missing in SparkR. One of the most important one of which is apply.

In R, apply acts as a nice substitute for having to loop over a data.frame by working over the margins, or row/columnar boundaries, to act on individual “cells.”

SparkR can’t work with objects at the cellular level because of its distributed nature, and the passing back and forth between JVM processes ,which means it’s just now starting to implement apply.

There are a couple of SparkR native functions, gapply and dapply, but neither of those do the same exact work as apply does, and there are all sorts of workarounds that don’t always get there.

And finally, model objects don’t have nearly the same accessibility as their analogs in R.

For example, one of the standard outputs for K-means clustering in R is WSS and available components, objects of the model easily accessible:

(check out the R API and SparkR API for kmeans)

set.seed(20)

irisCluster <- kmeans(iris[, 3:4], 3, nstart = 20)

irisCluster

K-means clustering with 3 clusters of sizes 46, 54, 50

Cluster means:

Petal.Length Petal.Width

1 5.626087 2.047826

2 4.292593 1.359259

3 1.462000 0.246000

Clustering vector:

[1] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[35] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[69] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1

[103] 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

[137] 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

Within cluster sum of squares by cluster:

[1] 15.16348 14.22741 2.02200

(between_SS / total_SS = 94.3 %)

Available components:

[1] "cluster" "centers" "totss" "withinss"

[5] "tot.withinss" "betweenss" "size" "iter"

[9] "ifault"

SparkR does not give WSS as an output, and does not make model objects available in the API, which means a workaround where code is pushed down locally is required to find out the optimal cluster size:

model <- spark.kmeans(df, ~ Petal_Length + Petal_Width, k = 3, initMode = "random")

summary(model)

[1] 3

$coefficients

Petal_Length Petal_Width

1 4.925253 1.681818

2 1.492157 0.2627451

$size

$size[[1]]

[1] 99

$size[[2]]

[1] 51

$size[[3]]

[1] 0

$cluster

SparkDataFrame[prediction:int]

$is.loaded

[1] FALSE

$clusterSize

[1] 2

## Workaround for WSS:

wss <- (nrow(rdfsample)-1)*sum(apply(rdfsample,2,var))

for (i in 1:9999) wss[i] <- sum(

kmeans(rdfsample, centers=i)$withinss)

plot(1:9999,

wss,

type="b",

xlab="Number of Clusters",

ylab="Within groups sum of squares", xlim=c(0,10))

Inability to plot data

Plotting data is the key to exploring and understanding for data science, and R is very good at it. If I have a project that’s small enough to fit on my laptop and has no external dependencies, I’ll usually choose R over Python for plotting, because, although Python has so many possibilities, they are not as well-developed as R.

SparkR has a port of ggplot2. Unfortunately, this project hasn’t been updated in a year, and is no longer compatible with the latest version of Spark.

This means, if you want to visualize something, you have to push it down into a data.frame. In general, this makes sense: Spark means processing hundreds of thousands, potentially millions of rows of data which means you have to summarize the data you’re working with before you do so. But, even when you summarize, you can’t visualize a subset in SparkR, interrupting your workflow.

Or, you could potentially push to a Zeppelin notebook, which means additional configuration.

Neither of those options are optimal for exploratory data analysis, a crucial task when working with data in any system.

Granted, plotting is a bit raw for all Spark APIs, but this is not the case in PySpark, which has Plotly.

Visibility into debugging

A lot of things happen when local R code is converted to a SparkDataFrame and as it makes its way back.

- R opens port and waits for connections

- SparkR establishes connections

- Each SparkR call sends serialized data over local connection and wait for response

- Methods done by the JVM process

- R-> JVM serialized binary data

- Types converted to lists

- Method + arguments are serialized, sent to backend

- The method is resolved.

This means that if something goes wrong in your code, it could be in any one of the following places:

- R native code

- Serialization of data to SparkR

- Conversion to JVM

- Movement from driver to executors

- Actual Spark job

- results

This is a completely different paradigm for R users, particularly ones not familiar with distributed computing, to understand. There is a huge learning scale, potentially larger than for engineers with no statistical background coming from other languages. The serialization/deserialization process means that there are many layers you need to understand and dig into when your code errors out.

The problem could be in the SparkR syntax; i.e. a function is unsupported. The issue could be in the serialization to JVM code. The issue could be in the network. Or, the problem could be in the still-developing SparkR codebase.

In order to understand errors, it’s important to become familiar with Java stacktraces, which are completely different from the error codes that R generates.

Incomplete Documentation

All of these are major issues that lead me to believe that potentially having R on the Spark platform is not generally a good fit for trying to square the circle between distributed computing and R.

But, all of this wouldn’t be so bad SparkR had better documentation.

As Holden Karau notes in “High Performance Spark”, Spark documentation can be uneven. As with all young projects, most of the documentation is either in the source code, or on the project’s page. To add to this, the SparkR API documentation is good, but not as detailed as PySpark or Scala.

The documentation available on Apache is somewhat comprehensive, but does not give nearly enough examples, and is missing a few big caveats that make it hard for a beginner to navigate.

This is particularly daunting for beginners coming from statistical computing who are trying to understand both how Spark works, how SparkR works, and nuances of the API.

The biggest issue I found missing was the lack of clear documentation that the SparkSQL context had been deprecated in Spark 2.0:

Spark’s SQLContext and HiveContext have been deprecated to be replaced by SparkSession. Instead of sparkR.init(), call sparkR.session() in its place to instantiate the SparkSession. Once that is done, that currently active SparkSession will be used for SparkDataFrame operations.

The sqlContext parameter is no longer required for these functions: createDataFrame, as.DataFrame, read.json, jsonFile, read.parquet, parquetFile, read.text, sql, tables, tableNames, cacheTable, uncacheTable, clearCache, dropTempTable, read.df, loadDF, createExternalTable.

and there are a lot of dead-end answers to that effect that still reference Spark 1.6 on StackOverflow.

Another issue that I spent a lot of time chasing down was name conflicts, which, like other caveats, should be easier to read and clearer up-front.

Conclusion

SparkR holds a lot of promise as a gateway into distributed computing for data scientists who are used to the R/RStudio workflow. But, the problem is that the way R works and the way Spark works are orthogonal to one another, and it’s not clear that it makes sense to try to “parallelize” them.

Hopefully the commit velocity means this is a project that’s of priority to Spark maintainers, and that the largest issues, including those of inaccessible model objects and additions to the modeling API, as well as clearer documentation, are resolved.

Thank you to Mark Roddy and Jowanza Joseph for reading versions of this.