Everything I learned about accidentally running a successful tech conference

On December 15, 2022, the first and only Normconf, the tech conference about all the stuff that matters in data and machine learning but doesn’t get the spotlight, happened.

**All the talks, the lightning talks, and hallway track talks are here. **

The event was a 15-hour long event split into three sessions hosted by 2 MCs, free and streamed on YouTube. We “sold” over 7,000 tickets, and through optional donations with the purchase of tickets, we raised $15k for NumFocus, the foundation for scientific computing tools that power a lot of the work in modern machine learning and data.

At its peak, we had almost 740 people watching live, and all in all over 10k people tuned into the livestream over the course of the day. Oh, and we also ran a Slack that, at present count, has 1400 members.

We sold merchandise, including a shower curtain that became the defining symbol of the conference much more popular than anticipated. We had, along with the other talks, a runaway hallway track where people actually gave talks in their hallways, autogenerated bingo cards, custom Slack emojis, and much, much more than we ever expected.

I accidentally dreamed Normconf into existence and, along with co-organizers Ben Labaschin, Guenia Izquierdo, Jeremy Jordan, and Roy Keyes, an enormous list of talented speakers, volunteers, MCs, community moderators, lightning speakers, and sponsors, made it happen.

It won’t be happening again for reasons I’ll outline later in the post, but I do want to offer some takeaways for people who are thinking about how to run online conferences and communities and create vibrant and happy online spaces.

Just by sheer metrics, it was a success - we even got a positive NPS score on Eventbrite!

And, first-hand accounts, it was a tremendous success, even more than we imagined it would be. I didn’t believe it myself at first, so I asked in Normconf Slack. Here is some bulleted feedback:

- The vibe was amazing, it was informal and very entertaining.

- the talks were great because for one they were not (at least not mainly) about the theory but more about what happens in practice. I usually go out from a conference and I still have to spend several hours to apply what I learn. Here I feel I could apply some of the tips tomorrow in my job

- The existing relationships between the organizers on display without making the conference feel cliquey – it’s clear folks are very comfortable with each other, and there are in-jokes that not everyone is part of, but it came with an openness that made everyone feel invited to the party.

- The schedule was clear and timezone-accessible

- all of the talks (lightning and regular) were really high quality, cohesive in structure and context, scheduled in a meaningful order, and presented by great speakers

- Engaging speakers with minimal jargon

- single track was refreshing, zero stress to figure what to watch and it focused the topic of attendees chatter in slack

- [I appreciated] The sense of humor and laid-back attitude, very chill conference.

- Overall the accessibility of the conference felt like a strong theme overall. Excuse the corniness of it, but it had strong feelings of a “conference for the

peoplenormies”. And I think that made it feel more approachable and ultimately a success in people actively engaging and being enthusiastic about being a participant.

How did we get here?

NormConf: Origins

I’m a machine learning engineer and, in August, my Twitter feed fills up with people being accepted and rejected from NeurIPS, which used to be a small academic deep learning conference that has become one of the most prestigious in machine learning. This year it took an extra-long time for people to find out, and my feed was just miserable, waiting to find out if they’d been validated.

If you go to the proceedings of any academic machine learning conference, you’ll find really impressive titles about neural networks, math equations, and parameters beyond your wildest dreams. The same is true if you go to any machine learning industry conference: you’ll find people doing billions of rows of realtime streaming, of complex feature stores, of vector search.

All of these conferences, while interesting and ones that I attend, are more aspirational than practical. I found myself wishing for a conference that covered the actual partial parts of machine learning: I wanted a conference that showed me what I do every day.

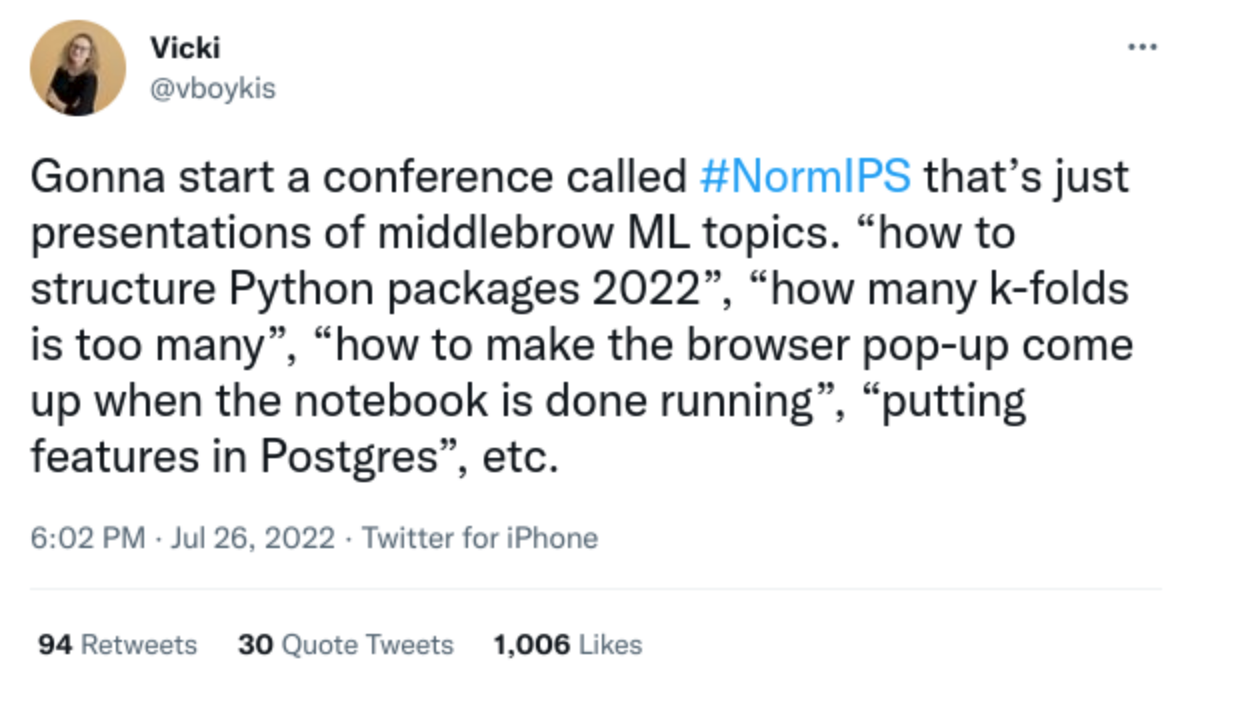

So I wrote a joke tweet:

The main reason I’m on Twitter (or whatever used to be Twitter) is to write joke tweets about tech, so I was ready for a string of “haha” reactions. What I was not ready for was people genuinely excited for this to happen. The responses to the tweet over the next 24 hours were, more or less, uniformly, “I know this is a joke, but can this please be a real conference?”

Sometimes, there are things that you decide intuitively without having to deliberate long at all, and, knowing that this would be a long, uphill learning curve and would take a lot of work, I still said yes, and thus NormConf was born.

Why “Normconf”? Because I already have a newsletter, called Normcore Tech, which has the same vibe of demystifying what is mystic, of taking technology apart to its core components, and it seemed fitting that the conference have the same name, although I was pretty adamant that it have its own branding, separate from me. I didn’t want the conference to be VickiConf but to be reflective of both the community and the people planning it.

A Conference is a Startup

Immediately, Ben, Guenia, Jeremy, and Roy volunteered to help run this thing, and a bunch of other friends in the data industry said they would help. At that point, none of us had ever organized a conference or any idea of what it would take. We started a Normconf Slack to organize the planning.

What it ended up taking:

- Four months of planning, from August when my tweet went up, to December 15, when it happened

- Creating organized SMEs responsible for

- marketing,

- Setting up and running the website, creating merch, doing giveaways, and running the twitter account

- community,

- Writing a code of conduct, deciding what would be appropriate in Slack, figuring out how and when to open Slack to conference participants, figuring out moderation, and how sponsorships would work with community conversations

- Sponsors,

- Creating a prospectus, answering sponsors that approached us (we didn’t solicit any sponsors, they all came to us!), signing contracts, etc.

- Ops,

- Figuring out how we would run the conference, which platforms we would use, how we would run MCs and moderators, how long the conference would be, and all the other day-of logistics

- general running the conference, with every larger decision eventually going through me. It only made sense at this size. Anything bigger and I would have gone insane.

- marketing,

- We organized channels for each of these in Slack and continuously updated to-do lists and shared documents. The conference was run and organized entirely out of NormConf Slack and Google Docs.

- Running the conference through my LLC, Averital Consulting (Strongly recommend you get one if you are running a conference.)

- Consulting people who had put together successful online events before (particulalry in the Python data community, Strangeloop, and other events.) and who had experience in running and moderating large online communities (thanks, Randy!)

- Looking to inspiration to other “fun” conferences, particularly BangBangCon.

- Calling in reinforcements and asking for help A LOT

- Being cognizant of the fact that everyone involved had day jobs and other commitments like children, sick children, moves, work travel, and other life stuff

All of this was a ton of work, but there were a couple of things that I think made running it easy and sometimes even fun. The first is that running a conference you believe in is a lot like running a startup: you have a bunch of very smart people and very little structure. If you want to talk to someone, you just do it. If you want to work on an idea, you execute.

Roy wants to give away shower curtains? Go for it! Jeremy wants to write a sponsor prospectus? Maybe read up on prospectus, then do it!

The conference sells itself

The goal of most conferences is to make money. As such, they need to first seek sponsors and sell tickets. They need to have guidelines. Our main goal of the conference was not to make money or reach some critical mass. We didn’t really care or keep an eye out for any of this, and in fact we thought we would have 500 attendees max. We cared mostly about making sure we had good speakers, good content, and a good community around the conference. We were fine with low-volume everything as a result. Since the conference was so low-stakes, we could move extremely quickly.

As a result, because we weren’t trying hard to draw people, the appeal was, antithetically fairly easy to achieve because the vibe of this conference was so salient and tangible I could sell it based on that alone. “Imagine a conference where we talk about the really day-to-day stuff that happens in the industry. If it sounds interesting, feel free to join we’d love to have you,” is so appealing that it’s easy to sell to both speakers and attendees.

With respect to audience, that was already also easy: I already have 35k followers on Twitter who trust me that I have normcore takes on most topics and who also provide a captive audience for my corny ML jokes (sorry). If you like this kind of content, you’re going to like NormConf, and so by virtue of self-selection, both speakers and audience alike were drawn into my fateful web.

With respect to speakers, between the five of us and our extended networks, we know interesting and funny people who will talk about these topics to audiences, so it was very easy to get speakers who had plenty of opinions on this.

And, regarding costs, since we planned an online conference, we were able to keep costs fairly low. We didn’t have to pay for a venue. Our largest costs were:

- High-quality microphones and ring lights for all speakers that needed them so that we could have high-quality recordings to share afterwards

- A videographer to make these recordings happen

- Marketing: logo design (thank you Barbara) for both the website, color scheme, and slide decks, which a lot of people ended up using for their talks

We are serious people who don’t take ourselves seriously

As organizers, we are already highly-driven, self-motivated professionals who put a high premium on execution. In normcore terms, we like to get this done. Personally speaking as someone who likes to execute, it’s very easy to work with a group of people who also self-select for execution. Even more than easy, it is a pure pleasure. One of the things I love the best is working in small teams that ship quickly. It gives me meaning and purpose. And I was so, so extremely fortunate that this group of people self-selected to do Normconf with me.

What made this easier was that we are all technically savvy. We work as machine learning and data engineers, so it was easy for us to do things like setting up and admining a Slack instance, setting up github and a website, figure out which streaming platform to use and how to use it and make decisions around hundreds of technical aspects of conference planning. The website development which Roy headed and the API which Ben built all happened through GitHub PRs that we tracked in Slack.

Yes, and……

In addition to a “getting stuff done” mentality, what really helps is that people are willing to understand that things can go wrong and will, and take this whole bizarre thing with a grain of salt. Should we have a live band play during an intermission? Sure! Not ridiculous at all. Let’s research some bands, should they be classical or mariachi? Should we give away stickers? Why not! We know a guy with a sticker platform. A lot of the success of the conference comes from the willingness to improvise, be flexible, and have a sense of humor about things.

The people that did this the best were the poor, poor MCs who kept the conference going hour after hour. Improvising around technical snafus, speaker time limitations, with audience participation and making sure as many questions as possible got answered, James, Jesse, Ben, Randy, Caitlin, and Chris did an amazing job keeping things moving for the audience as we fiddled with tech on the backend.

Normcore Technologies

Someone said we were running the “normy” Tech stack: Slack, Zoom, GitHub, and YouTube. We briefly considered using a conference platform but bailed when it cost too much. Ultimately we decided to use the tools we and most of the people who are conference participants use the most, both because they were familiar to us, and also because they cost the least, and because we didn’t want any surprises. We didn’t want to sign up for or learn new things, and luckily our evaluation criteria meant that we could move quickly in the stack we were comfortable with. Many attendees and speakers also said they were happy to have to not figure out new tech to tune in to speak, and also tune in throughout the day.

If you are planning a conference, consider using what people already know and have.

The community

Community was crucial for us. We wanted to invite as many people to to the table as possible and for everyone to feel welcome. As such, we spent a lot of time thinking about the best way to prevent bad actors and make sure as many people got to participate and feel as part of the event as possible. We did this in several ways.

First, we set the ground rules for Slack, made sure everyone who signed up went through a “welcome” prompt that asked them to fill out their profile and their face and introductions, and opened Slack early to get people talking to each other before the conference.

Then, on the day of, we deliberately made the conference 15 hours long so that as many possible people across the world could tune in live as possible. This took a big toll on the organizers, MCs, moderators, and speakers, but I’m hopeful that that was balanced out by people who would not have otherwise participated, participating.

Randy described this really well in his post recapping the conference,

While social media was definitely a thing, with people tweeting and tooting about the event throughout the whole day, the center of the whole event was the conference Slack that had over a thousand users registered to it at the peak. Also important to the experience was that while the slack had tons of channels for memes, sharing work, and asking questions, everyone gathered in the central #general channel for talking about the conference was it was going on.

On top of audience participation, the speakers and MCs were also actively monitoring the chat rooms, often while on air, to provide a feedback loop between the audience and people visible on screen. Often, someone would pose a question, the MCs pick it up to ask on stream, the speaker would answer it, and while that’s happening, other people in the audience would chime in with their own answers. Such interaction is not even possible in an all-in-person format. It’s much more a community than even a traditional talk experience.

Behind the scenes, to keep up with the flurry of messages, the staff had been watching the chats for questions and threading them so they wouldn’t get scrolled off before MCs could notice. Staff sometimes even provided some questions on their own in case some gap-filling time was needed.

It’s not particularly difficult work, but it’s definitely a team effort to keep the production running as smoothly as it did.

The Vision

Aside from the immensely hard work of everyone who organized the conference, the help of our sponsors, and the community, I think what made this successful is, honestly, that normcore technology is not a shtick for me. It’s genuinely how I think about solving engineering problems, and when I go back to my posts and my tweets, it’s evident very much that it is my M.O. Normconf, is, basically, my ethos, and as such I couldn’t have made it any other way.

Normconf was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen in the data community, and I’ve been around a lot. But there is one problem with a small conference that is a success: next year, people will expect it to be a larger success, and as everyone knows, and as Elon Musk is learning with Twitter currently, good things, especially good things where you have to moderate people, don’t scale.

I don’t want to spend next year looking for sponsors, making sure we have enough moderators, watching Slack, finding speakers as good as this year’s. This year there were no expectations. Next year will be all of them.

And thus begins and ends Normconf. I have created it, and I am setting it free into the wild.

I want to say this was an amazing experience, a labor of love, and because it was so good, we’ll never be able to top this, and I will never do it again.

Thank you, thank you, thank you to everyone. This was without a doubt the highlight of my year and I am grateful I could end it like this, with you.

Next year I’m taking a step back from building community to build Viberary. See you on GitHub and see you in 2023!