One Friday when I was in fifth grade, I bombed a math test. I’d gotten something like an 81, an unforgivable grade in a Russian immigrant family. I remember sitting on the bus, my whole stomach filling with dread at the thought of sharing this grade with my parents.

Kids sat around me on the bus, laughing, the whole weekend full of promise ahead of them. Mine stretched out bleakly before me, my fate and entire future uncertain, the exam with the bad grade sitting there quietly in the backpack next to me.

What made it sting is that I studied for the exam. I studied for every exam. I would sit for hours upon hours at homework that sucked all the joy out of learning and focused more on rote memorization of series of steps, one of which I was always bound to get wrong because I left out a negative sign somewhere.

I went through my attic a couple weeks ago and found boxes and boxes of flashcards and study sheets with formulas and equations labelled neatly, “ALGEBRA - EXAM 2”, “GEOMETRY MIDTERM” in a rickety, girlish hand. I remembered writing out those flashcards at 2, 3 in the morning, crying, wondering why none of it clicked and why my answers always came out wrong on the exam.

Math for me was always something to hate and fear, a series of sequences that needed to be performed “just because.” I got ok grades in math, but only through sheer willpower and sitting and memorizing and writing equations until I fell asleep at my textbooks.

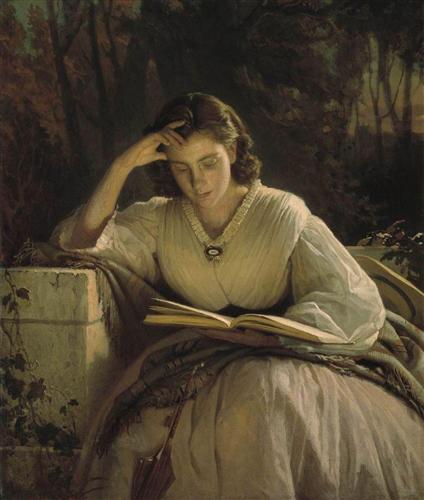

I would always rather be found with a novel in hand. Books made sense. Instead of sitting dead and mute on the page like so many polynomial functions, they talked to me. They took me to new worlds. They explained things. Books and their authors were the constant companions of my childhood.

At first, books taught me about myself. Baby-Sitters Club taught me about American suburban culture and middle class American social norms that I couldn’t pick up from my immigrant family. Judy Blume taught me that there were kids like me who were half-Jewish and who had a lot of the same questions about God as me. Redwall taught me about bravery, and, more importantly, that somewhere out there imaginary talking mice and badgers were eating much better than me.

Then, books started to teach me about the world. I remember first reading Confessions of an Economic Hitman and The Lexus and the Olive Tree and slowly feeling like some of the pieces were clicking.

Finally, it appeared that the world wasn’t a series of random events that just happened: there were systems and rules that could be used as guidelines in determining how events would play out. Rules of thumb like : the universe abhors extremes and will always move to the middle (balance), it’s important to never feel comfortable in where you are, because as soon as you do, something will change (agility), and if a person is successful at one thing, they are horrible at others (allocation of time) began to shape my worldview.

As I spent more and more time with books, after high school, I swore off math forever. But then I realized I needed math for my econometrics classes, and later, for the linear algebra that lay hidden underneath much of SQL and spreadsheets, I started to realize that math was trying to talk to me, too. Math spoke much more quietly than books, and had a different approach. But one that was just as important. It was incumbent on me to learn enough to listen to what it had to say. If I did, it would make my life infinitely easier.

Instead of being mysterious, mathematical models now became systems of processes I could use to understand the world and explain it. Black swan events. The pareto principle. Decision trees. All are important concepts that are reflected in very real human behavior: The collapse of the stock market, how the medical system functions, how child development works, why it always takes a little bit of time for food to come at a restaurant, what today’s weather will be, how fast you can lose or gain weight, how much you should save for retirement, why a Beyonce concert ticket costs so much.

I hate sounding like a dorky magazine that’s trying really hard to get kids into math and science, but once I realized that math really is all around us, I started thinking about it much more.

Spending time with books means having a conversation with their authors. The best authors talk to you and you learn something new from them, coming away from a book as you would from a friend, refreshed, replenished.

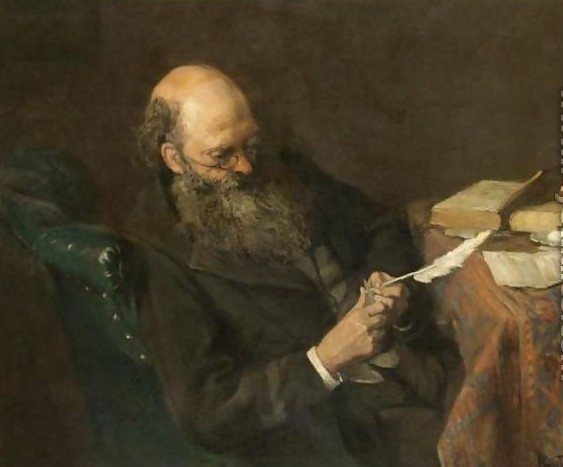

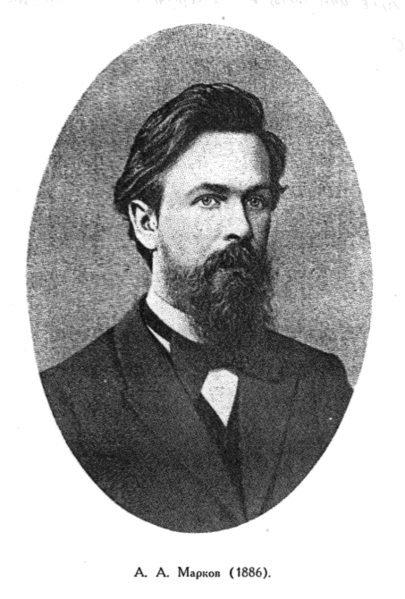

Spending time with math means gaining an appreciation for the people behind the formulas. For the past twelve weeks,for a work project, I’ve been hanging out with Andrei Markov. He’s the Russian mathematician responsible for creating Markov chains, the algorithm that, in a modified form, powers PageRank, which powers Google, which powers the internet as we know it today.

Markov chains predict the next action in a given group of possible actions based on the probabilities that the transition from one action to another could happen.

For example, in weather forecasts, the probability that tomorrow will be sunny given that today is cloudy is based partly on the probability that other similar sets of days have occurred previously. It’s a little more complicated than that, but that’s the gist of it.

There is something about spending a lot of time with a person’s concept of the world that really makes you feel close to them. As I’ve been working through implementing Markov chains, I’ve been struck by how quietly elegant his thinking was, and how clear his reasoning about how events are linked by underlying forces in the real world.

Markov believed that the world is messy, but given enough abstraction and some important guidelines, we can wrestle order out of it and offer some predictions about how the world will be. He proved that we don’t need much to make predictions, just the last state of events, but that that was enough. He believed in order and logic, in quiet reason. This much is clear from the way Markov chains work.

Markov’s world is pretty clear: There’s only a number of things that can happen, and we know the way they can occur. If we stick within the parameters of this world, we’ll be fine, even given a large amount of unknowns. It’s easy to appreciate this kind of beauty.

As I’ve been working through his logic, I’ve been thinking about what kind of person Markov was to create ideas like this.

He was born sickly and limped much in his early years (link in Russian), at times only being able to walk on crutches. He had an operation on his legs when he was just ten years old, and lived mostly inside his own head, as all great people do. He had a terrible experience in the discipline-heavy private school he attended. He didn’t like homework. He loved math. His brother, also a math genius, died when he was just 25 from tuberculosis.

Two men and a woman, 1910. Source.

Two men and a woman, 1910. Source.

He got married, he had children, and would have lived the quiet life of an academic if Russian history didn’t interfere. The early 1900s were rife with small revolutions that would eventually culminate in the events of 1917. Student revolutions, the war with Japan, Bloody Sunday - all were events that created chaos in the country, changed its social fabric, and destabilized the intellectual middle class.

Markov had the misfortune to be a principled man in troubled times. He was forced to resign from his position at St. Petersburg University because he refused to monitor students and report on them to the administration after a student-related strike. He also protested election into the Russian academy of Sciences, a great honor, because the Tsar didn’t like Gorky’s politics.

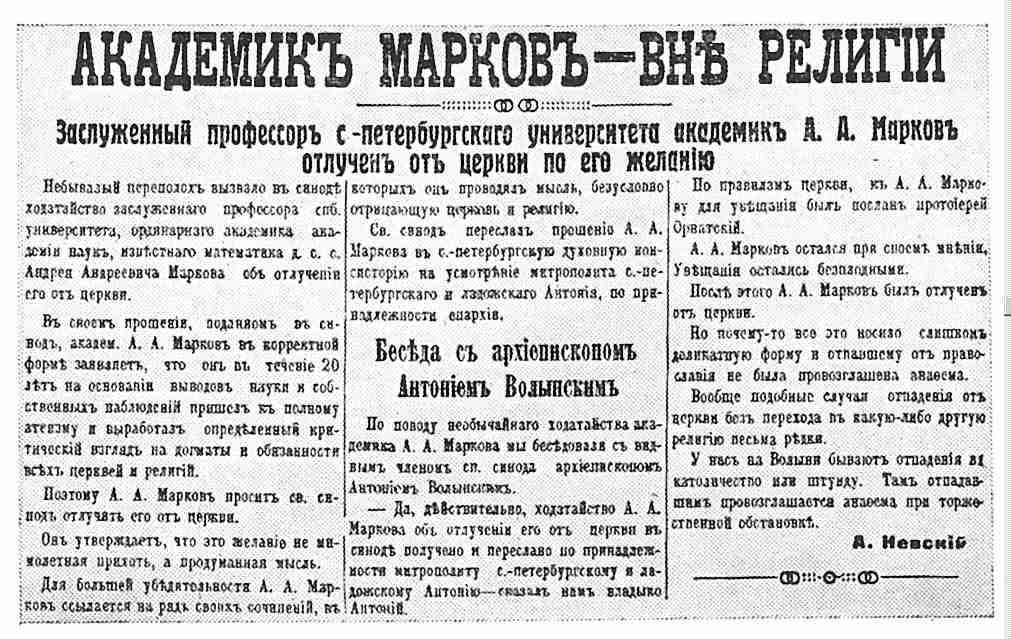

He later asked to be excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church because he disagreed with Leo Tolstoy’s excommunication:

I can’t help but think that all the instability, death, the feeling he had of being a social misfit greatly impacted Markov’s work. Not only did he work extremely diligently and frequently, but it’s possible that the algorithms he created, the same ones I’m using over a hundred years later, were meant as a bulwark of stability during a time when Russia and his own life were decidedly unstable. His childhood illness, his later-life crisis of confidence, his loss of faith - they all had to play some part in his understanding of the world, and I think, the more life threw curves at him, the more he felt compelled to control what made it onto the page and to model his understanding of the universe, and that makes me appreciate it even more.

The formulas I learned as I was growing up were rote memorization. Even my math teacher said, “You only use 10% of everything you learn in class,” meaning, “Cram this once and forget it.” But the way I came to math on my own, understanding algorithms as ways to understand and organize the messy, chaotic world, has been much more interesting. And thinking about the people behind these equations has made them all the more real to me.

If I could go back to those dreaded days on the bus, to those that girl during those nights spent slumped over my algebra book, and tell her, “This all really does mean something, it was created by people who cared just as much as you about understanding how the world works, and you’ll get to do it for work and it will be interesting and exciting and real people will benefit from it,” I would.

For now, this post will have to do.